The

turn. The bend. The twist. The corner. There were quite a few in

Alma’s family who had gone around it. She imagined it must be a sudden

angle in your thinking that you couldn’t see approaching in the way

that you couldn’t see the coroner on the street in front of you. It was

invisible, or nearly so; possibly see through, like a green house or a

ghost. This corner's lines ran a completely different way to all the

others. So instead of going forward, down, or sideways, they went

somewhere else, in a direction that you couldn’t draw or even think

about, and once you turned this hidden corner, you were lost forever.

You were in a maze you couldn’t see, and didn’t even know you was there.

Alan Moore

Non-locality changes the game. Non-locality is not about seeking the answer, it IS the answer. Once you have by chance or by design encountered it, the game becomes a bit more grown up. Now you have to face the answer. No more trips to Ceylon are necessary. No more parties in LA, no opening of chakras or revelation of shastras or passing of mantras or building of yantras is going to carry you any further than where you have finally arrived. You have found the answer,

and now you have to face it. And people just hate that. It’s appalling. It doesn’t feel like fun at all.

"The Answer" : here it is. What to do with it?

Terence McKenna

time is a hyper-dimensional confessional buried in a gardenpark matrix of distortion and rebirth, an eschatological cubehouse microfilming coincidental blasphememes that spark recursive nightmores of comicguilt triggering irrational

mountains of stoned criminals to rockslide into nursering schools for

remedial coursework in fractal doctrines of frogiveness and Space/

Pepe

I, too, sing of a communication struggle here. I am trying to describe the unspeakable by moving the boundaries of what can be said and what can’t be said. Am I succeeding or failing? I know that every time I attempt to gather the freshly shed skin of synchronicity for approval, the first emotion I have is guilt, followed immediately by embarrassment. Because I am hideously unfaithful to a truth that I know can’t be told. But somewhere deep inside there is a voice that offers hope that this project has helped to create an object of discourse that can be returned to in various states of mind.

What this is is the tiling of an abyss, an attempt to shape a memory of perceptions felt after a brief flash of lightning in an endless void. No matter how much I am able to bring back, no matter how much detail I provide, it is still an incredible flattening. Language is not an adequate tool, which makes me painfully aware that the most high flown, hysteria provoking descriptions of non-locality I’ve ever been able to summon up were complete betrayals of the real thing. So not what it was that the word LIE is almost applicable. But it’s the best I can do.

Terence McKenna

According to McLuhan, how we process language is not a biologically determined thing. Language is a culturally determined thing. As we slowly migrate out of the shadow of a print controlled modality, our relatively empty heads are sensing what once was, how our heads once were: filled by an orchestra of individuated wonder. This is another attempt to help restore that.

"There is a doorway,” Emmanuel said,

“to her land. It can be found anywhere that the Golden Proportion

exists. Is that not true, Zina?”

“True,” she said.

“Based on the Fibonacci Constant,” Emmanuel said. “A ratio,” he explained to Herb Asher.

“1: .618034….The ancient Greeks knew it as the Golden Section and as the Golden Rectangle. Their architecture utilized it…for instance, the Parthenon. For the Greeks, it was a geometric model, but Fibonacci of Pisa, in the Middle Ages, developed it in terms of pure number.”

“In this room alone,” Zina said, “I count several doors. The ratio,” she said to Herb Asher,

“is that used in playing cards: three to five.

“True,” she said.

“Based on the Fibonacci Constant,” Emmanuel said. “A ratio,” he explained to Herb Asher.

“1: .618034….The ancient Greeks knew it as the Golden Section and as the Golden Rectangle. Their architecture utilized it…for instance, the Parthenon. For the Greeks, it was a geometric model, but Fibonacci of Pisa, in the Middle Ages, developed it in terms of pure number.”

“In this room alone,” Zina said, “I count several doors. The ratio,” she said to Herb Asher,

“is that used in playing cards: three to five.

It

is found in snail shells and extra-galactic nebulae, from the pattern

foundation formation of the hair on your head to—“

“It pervades the

universe,” Emmanuel said, ”from the microcosms to the macrocosms.

It

has been called one of the names of God.”

Philip K. Dick

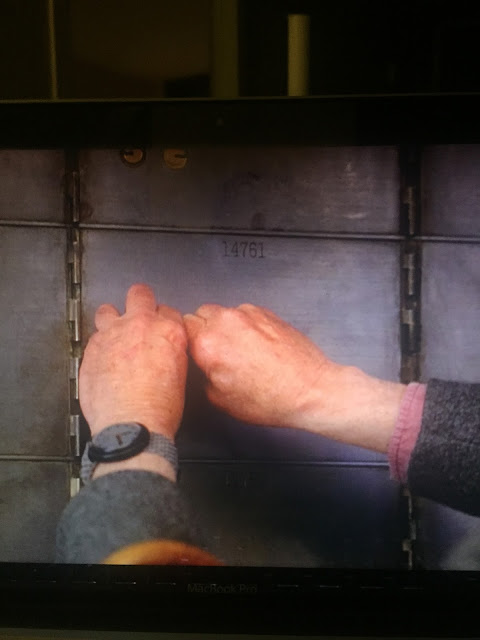

Crowley devised a clever symbol for this irrational doorway. Seen locally, rational twin siblings. Non-locally, the eyes and ears of the rabbit:

The rational twins fight and fuck and flail and wail, taking axes to the doorways of their perceptions. The rabbit? The rabbit slips effortlessly into the non-repeating infinity of the golden dawn.

? !

The rational twins fight and fuck and flail and wail, taking axes to the doorways of their perceptions. The rabbit? The rabbit slips effortlessly into the non-repeating infinity of the golden dawn.