John Dee knew that the basic theory of proportion between microcosm and macrocosm came from Vitruvius and had directed his readers to 'looke in Vitruvius and find it there’. Robert Fludd was certainly familiar with both Vitruvius and Dee's Preface and, moreover, as briefly indicated at the beginning of this chapter, his whole musical philosophy of Macrocosm and Microcosm, his whole History of these Two Worlds, is imbued with the Macrocosm-Microcosm analogy expressed in terms of musical proportion. And this reminds us that we have left out one of the subjects of the technical history of the Macrocosm, both a Vitruvian subject and a Dee subject, and the most important of all subjects for Fludd: music.

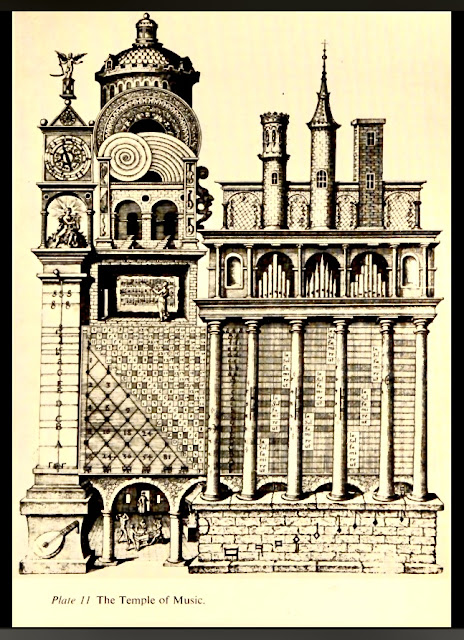

Music comes second among the sections of the technical history of the Macrocosm, immediately after the first section on number. On the mnemonic wheel, immediately to the left of the numbers to which the Ape points, representing Section 1 of the book, we see the man playing the organ, representing Section 2, on music. This section is introduced by a large folding engraving containing one of the most striking illustrations in the whole book. It represents a fantastic building called ‘The Temple of Music'.

This building is fundamentally a memory system for memorizing all the parts of the exposition of his music theory which Fludd gives on the following pages. Fludd's music theory has been studied by P. J. Amman who finds that it is 'antiquated in comparison with other musical treatises of the period but original in its presentation of the subject’.

The fact is that Fludd was still trying to be a universal man of the Renaissance; his music treatise is but one of his efforts in the volume and should be compared with his treatises on surveying, or painting, or machinery, though doubtless for him the section on music was the most significant and all-inclusive.

The symbolism of the Temple of Music is explained by Fludd in the description which follows the picture, from which the following is a translated quotation:

We imagine then this Temple of Music to be built on the summit of Mount Parnassus, the seat of the Muses, adorned in every part with eternally green and flowering groves and fields, sweetly watered by chrystal fountains whose murmur induces to gentle repose, frequented by birds pouring forth in song the sound of diverse symphonies. The nymphs around the temple, the satyrs in the groves taught by Sylvanus, the shepherds in the fields with Pan their leader, utter their choruses. Amidst these delights is the divine gift of Apollo who receives the adoration of all; whence arise on all sides peace and concord through the mysteries of harmony and symphony in which all the concords of the heavens and the elements are linked together. The whole universe must perish and be reduced to nothing in warring discord should these consonances fail or be corrupted.

Apollo with his lyre, whom we see sculptured on the Temple, thus represents music in a cosmic and philosophical, as well as a poetic, aspect. The presiding genius of the Temple, says Fludd, is Concordia. Its custodian or priestess is Thalia, one of the Muses, who is shown in an alcove on the upper level of the Temple pointing to a piece of music. On the ground level is an arched doorway through which a little scene is visible, smiths are wielding their hammers at a forge, and through a door on the far side of the building a figure enters mysteriously, holding a set-square. It is, as Fludd explains, “Pythagoras, represented in the moment of discovering the musical proportions and consonances through listening to the sound of hammers on an anvil.”

Music is here being presented both as a fundamental cosmic reality and as a mathematical art having its basis in proportion; and the Temple of Music is a striking example of the mnemonic-symbolic basis of Fludd's thought, which made the detailed illustration of his works, the presentation of his arguments in mnemonic-symbolic form, so important for him.

However singled out and emphasized because of its importance for his musical philosophy as a whole, Fludd's section on music conforms to the general plan of the technical history. It gives the theory of the subject as a mathematical art, basically connected with number like all the subjects, and it gives illustrated information about practical applications of the art.

The strong practical bent of Fludd is nowhere more apparent than in his chapters on musical instruments; these include stringed instruments, wind instruments, percussion instruments.

Particularly striking is his application of his mechanical bent to the invention of music-making machines. He claims to have invented new instruments and music-making devices, such as the remarkable looking object described as 'Our Great New Instrument'.

The musical instruments and inventions are fully illustrated and these illustrations must be seen in the context of the whole rich illustration of the book to realize that Fludd, the universal man, can turn his hand to surveying, perspective painting, mechanics, and machines, as well as to music-making.

It is possible that music may have been Fludd's strongest subject. He was interested in singing, and mentions a Friar Robert Brunham whose notation for singing he has used, and perhaps he could play the musical instruments which he illustrates. As an adviser on music, Fludd could have been in demand by theatrical producers and at courts. In another of his works he states that his musical inventions were received with sympathy by the musicians of the court of the King of England.

There is a point about the symbolism of the Temple of Music in relation to music theory which may be important. The most noticeable features of the Temple are those great spirals under the dome, with two doors below them. Their meaning is thus explained in Fludd's text accompanying the engraving:

Thou shouldst carefully examine the spiral revolution in the largest tower which denotes the movement of the air when struck by the sound or the voice. The two doors signify the ears or the organs of hearing, without which the poured-forth sound is not perceived, nor can there be entry into this temple save by them.

Surely (a point not noticed by Amman) this is a visual representation of Vitruvius on acoustics in the theatre, on those undulating circles of air on which the voice is carried, wherefore 'the ancient architects following in nature's footsteps traced the voice as it rose and carried out the ascent of the theatre seats.

Fludd is following Vitruvius, not only in treating of music as a Vitruvian subject but also in introducing his treatment of music in the context in which Vitruvius had treated it. For the exposition of musical theory in Vitruvius comes in connection with his discussion of the theatre and of the 'sounding vessels' which amplified voices in the theatre.

The musical theory expounded by Vitruvius is based on that of Aristoxenus, an Aristotelian rationalist philosopher who was not in the Pythagoro-Platonic tradition. On the other hand Vitruvius's plan of the theatre, based on zodiacal configurations, introduces the idea of a cosmic music, or, as he says, a musica convenientia astrorum, and this accords with the traditional notions of musica mundana and musica humana descending from Boethius. Renaissance theory developed this side of the musical tradition, involving connections between musical proportion and cosmological proportion such as Vitruvius implies in his theatre plan, based on the musica con-venientia astrorum. Fludd, like Francesco Giorgi, is of course fully in this tradition.

As we saw, Dee had repeated Vitruvius on the sounding vessels placed under the steps in theatres and ordered according to musical harmonies 'distributed in the circuits by Diatessaron, Diapente, and Diapason'. This is the only allusion to an ancient building in Dee's Preface. The allusion in the Temple of Music to the voices rising on spirals of sound in the theatre is the only allusion in Fludd's technical history to an ancient building.

We asked why Fludd left out architecture in the technical history. The answer may perhaps be suggested that the Temple of Music represents architecture, represents music as architecture.

All the Renaissance theorists emphasize the connection, indeed the identity, of musical proportion with architectural proportion. The building shown by Fludd is of course not a theatre, nor are there any sounding vessels in it. Nor is it properly Neoclassical but a mixture in which the classical columns do not fit with the Gothic features. It does not represent any real building though it may reflect something of the architectural eccentricity of the Jacobean age. It is an architectural fantasia invented and, perhaps, drawn by Fludds as a symbolic expression of his musical philosophy and of the musical theory which he will expound on the following pages. But I am impressed by the fact that Fludd clothes music in this architectural form, suggesting that he is thinking of a connection between architectural and musical proportion. And though this is not a theatre, ancient or modern, some of its leading aspects were certainly suggested by passages in Vitruvius on the ancient theatre and its musical expressiveness. Tantalized and mystified we gaze and gaze, noting the dome and the lantern, the circle of the angelic choir beneath it, the airy spirals carrying the sound to the ears.

And that large mask on the wall, does it refer to the figure of Thalia, the Muse of Comedy, and carry with it a suggestion of the theatre? And below, there is that room which extends right through the building to the back, where Pythagoras enters and hears the mysterious sounds.

Whatever one may think of Fludd's musical theory or of the peculiar architecture of the Temple of Music, this Temple is surely an impressive symbolic statement of the psychology of a

musical philosopher, of one whose outlook on Man and the Universe, on Macrocosm and Microcosm, finds its deepest expression in terms of music.

This chapter has attempted to bring out a side of Robert Fludd which has not been generally recognized. Though, as in the case of Dee, historians of science are becoming increasingly interested in Fludd who is no longer regarded solely as a wild and hazy figure, it has not been realized that in one aspect of his thought he belongs into the mathematical, technological, and Vitruvian tradition stimulated by John Dee.

As I have suggested earlier, it is even possible that Fludd may have had access to Dee's papers. These are known to have been dispersed, and sought after by his son in the early seventeenth century. Some of them came into the hands of Sir Robert Cotton, whom Fludd knew. Among the titles of unpublished works of his which Dee lists one finds, for example, Trochlica inventa mea, indicating some treatise on wheel-mechanisms (perhaps expanding his notes on this in the Preface), and De perspectiva illa, qua peritissimi utuntur Pictores, indicating a lost treatise by Dee on perspective for the use of artists. Some of the titles of Dee's missing mystical works sound to me also extremely close to the categories of Fludd's thought. To explore this theme of possible dependence of Fludd on Dee in many ways would require a book in itself and I do no more here than raise it as a question.

What can however be said as a result of the preliminary researches in this chapter (preliminary in the sense that I hope that others will carry them much further) is that there is a continuous tradition of Vitruvian influence in England, operating in both John Dee and Robert Fludd, that this tradition connects with technological development, and in particular with the technologies needed in the developing art of the theatre.

Frances Yates, Theatre of the World